The Murder in the Red Barn at Polstead is as notorious today as it was when it was committed almost 200 years ago as Ross Gilfillan explains...

Gaol, workhouse, police station and Bridewell, Moyses Hall in Bury St Edmunds has been many things since it was first built in the late 12th century.

Now the town museum, this Norman arched building, with its narrow passages, stone floors and jail-barred doors is atmospheric, perhaps even spooky. It's an impression intensified by some of its more outlandish exhibits.

Barely across the threshold and the visitor is confronted with the iron gibbet, which once held the rotting remains of a criminal's cadaver. But this isn't the most gruesome item on display, not by a long way.

Nor does that questionable honour go to the scrap of leathery human scalp, or to the death mask of a convicted criminal. Also out of contention is the graphically-detailed bust, made directly after this man's execution by hanging, showing features that are puffily bloated and veins swollen by slow strangulation.

Strangely, the prize for grimmest artefact here is deserved by a book, the account of a famous local trial. It is bound in tanned human skin.

The skin belonged to the same luckless felon whose bust, scalp and pistols compete for the attention of tourists, scholars and ghouls, for whom the legendary Murder in the Red Barn remains as fascinating as the day William Corder committed it in 1827.

If this all sounds a little melodramatic, then we should remember that what is commemorated here is the most infamous murder of the 19th century, a case which quickly became the subject of newspaper tirades, ballads and broadsides, street corner sermons and, of course, stage melodramas themselves, versions of which continue to be performed to this day.

This is not so surprising when we consider the key elements of this tragedy. Firstly, there are its players: a (supposedly) innocent female victim; her seducer and murderer, a predatory young squire, and the stepmother, whose weird dreams led to the discovery of Maria Marten's body beneath the floor of a village landmark called The Red Barn.

Also a gift to newsmen and dramatists would have been the ways in which the murderer was rumoured to have carried out his black-hearted deed, variously by shooting, stabbing and strangulation.

No wonder this is a story which goes on being told, in one form or another.

But what is the reality behind an event which has held the public interest for almost 200 years? Is the true story a little more prosaic, a little less interesting than the myths which have sprung up around the events?

Amazingly, no. The story of William and Maria, with all its twists and turns, actually lives up to its accumulated hype. What really happened was this.

William Corder was born in 1804, the son of a prosperous tenant farmer, in the village of Polstead, in Suffolk. Nicknamed Foxey in school, Corder was articulate and bright, but given to lying, cheating and occasionally thieving.

Though no great drinker, he liked the company of women and if entertaining them meant fraudulently selling his father's pigs or, on one occasion, forging a cheque for 93, then that was the way it must be.

His father, who appears to have favoured his other sons, despaired of him and despatched him to London to find work or go to sea. Unable or unwilling to find a position, William fell into the company of petty criminals and squandered the money his father had provided for him. The prodigal was recalled to Suffolk when his brother Thomas was drowned while trying to cross a frozen pond.

It was Thomas Corder who had first connected the family with that of Thomas Marten, the village mole catcher. The 17-year-old Maria in parish records was pretty, literate and, having already been passed down the clothes of her employer's daughters, had developed a taste for finer things.

There's a story that a fortune teller told her that though she wouldn't reach old age, she would have many lovers and that riches lay within her grasp. She was wrong only about the riches.

Once Maria had become pregnant with his child, Thomas dropped her like a hot brick, leaving the way clear for another lover, Peter Mathews, a good-looking, middle-aged man with connections to the owners of Polstead Hall. Maria's affair with Mathews continued after the birth of the child and its subsequent death, only weeks later.

She bore Mathews progeny, Thomas Henry, in December, 1824. Like Thomas Corder, Mathews too quit the stage, but agreed to pay a quarterly sum towards the child's maintenance.

Soon after William had returned from his spree in London, tragedy struck the family. In a short space of time, his father and three brothers were all dead, leaving William to run the farm with his mother.

His new responsibilities didn't prevent William from looking about for interesting distractions and it wasn't long before he took up with the comely but fallen Maria, who would have seen in him a slim, fair and fashionably dressed young man, another scion of the prosperous Corder clan.

But neither the Martens nor the Corders would have had much reason to celebrate the renewed connection. Thomas had left Maria in the lurch; Maria herself now had a reputation and in any case, was from the wrong side of the tracks.

The couple met furtively, often at the barn with the part thatched, part red-tiled roof, a half mile from Marias house. Their secretive relationship was threatened with exposure when Maria once again became pregnant.

Maria was naturally keen that Corder should marry her and at this stage he appeared to concur. William installed Maria in lodgings at Sudbury, nine miles distant, to have the baby. The infant died soon afterwards and rather than risk exposure and censure, William buried it in a field. It has been suggested that the child's death may not have been natural.

These were turbulent times for the couple. There was, for instance, the matter of the missing £5 note, payment to Maria by Peter Mathews, which had mysteriously gone missing. Maria accused William of stealing and cashing the note; William hotly denied it.

They argued about the burial of their dead child, they argued about William dragging his feet over their marriage plans. All this came to a head, fatally, one day in May, when William proposed that they elope to Ipswich, where they would marry without unwanted attention. They would meet in the Red Barn, he instructed her.

He added an element of urgency by telling Maria that a warrant had been issued for her arrest on charges of bearing illegitimate children. Because of this, she should disguise herself in men's clothing before meeting him at the Barn; she could change into her own things there.

Later, William returned from the Red Barn. Maria Marten was never seen alive again.

It was now that William began acting oddly; more shifty, very evasive. Questions were asked, lots of them. Where was Maria? Friends and family wanted to know. When he was obliged to give an answer, William said that Maria was in Ipswich. Then he said that she had gone to Great Yarmouth, where she was staying with a Miss Rowland. She couldn't return yet, he said, for fear of provoking anger in the village.

Some might have found this a credible excuse; the pairing of the squire's son and the unmarried mother wasnt a match made in heaven.

Then he announced that he and Maria were to marry at Michaelmas, 1827, but by the time late September had arrived, things had become too hot for William Corder, who quit the village, saying he felt unwell.

He went to London and made a visit to the Isle of Wight, from where he wrote home saying that he and Maria were happily settled on the island. He was sorry that Maria herself was unable to write, but she had hurt her hand. In another communication, he said he was puzzled that a letter Maria had written had not been received.

Back in London, William placed an advertisement for a wife in The Times and from over 100 replies, picked Mary Moore, a respondent he had already met on the Isle of Wight. They married in November, 1827 and soon afterwards, they set up a school for young ladies in Ealing, West London.

Unknown to William, as he settled to his new life, strange things were happening in Polstead. Maria's young stepmother had begun to talk about her troubling dreams. Her dreams proved amazingly specific and very helpful.

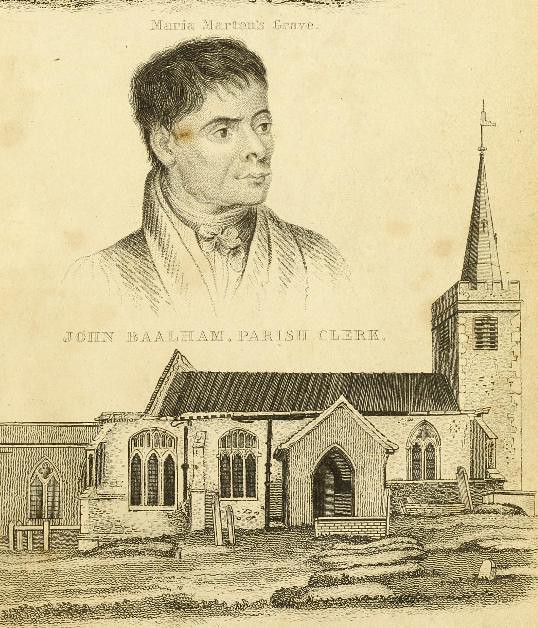

They told her not only that Maria had been murdered and buried in the Red Barn, but precisely where. Her husband was sent to the barn and after prodding the ground with his mole-spike, soon discovered the remains of his daughter, wrapped in a sack and buried in a grain storage bin.

An inquest was quickly convened at The Cock Inn, where Marias badly decomposed corpse was identified by her sister Ann from the clothes on the body, the colour of the hair and a gap in the teeth.

Tightly wrapped around the neck was a green handkerchief which had belonged to William Corder. The cause of death wasn't as easy to identify: clearly, she had been shot, the ball passing through her left cheek, but she appeared also to have been stabbed between the fifth and sixth ribs and on the right side of her neck.

And had the villain strangled her with his own green handkerchief? And who was to say he hadn't buried her alive?

That Maria Marten was shot seems beyond dispute, but it has been suggested that other wounds might have been caused by her father's mole spike or by the inexpert handling and examination of badly decomposed flesh.

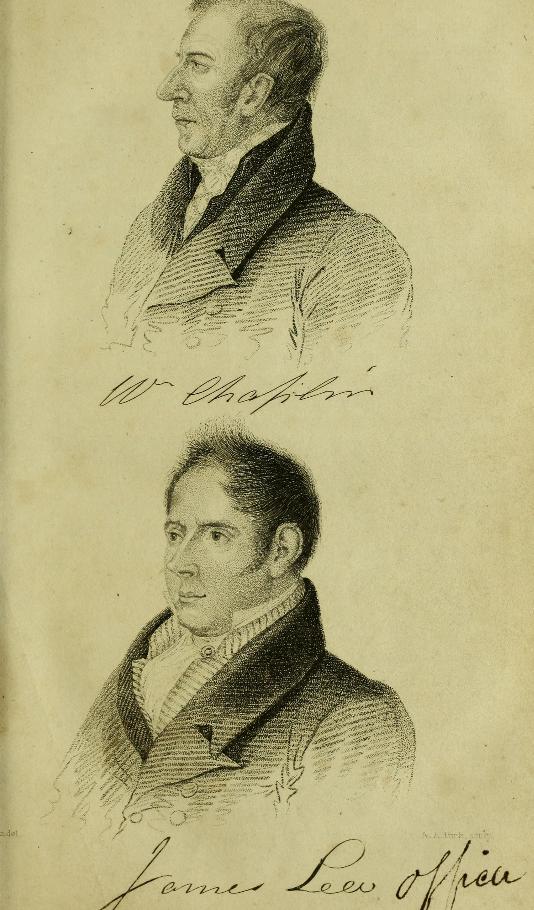

William would face charges on all these counts and more when he eventually came to trial. But at this point, the suspect himself was notably absent and a local constable called Ayres was asked to assist James Lea, a capable London police officer, in bringing Corder to justice.

Lea and Ayres tracked Corder to his new school in Ealing, where Lea gained admittance to the house on the pretence of having a daughter he wished to board there. William Corder was apprehended while engrossed in the business of timing his boiled eggs. When James Lea took him aside and explained the nature of their business, Corder at first refused all knowledge of Maria Marten. But a pair of pistols belonging to Corder were found on the premises, along with a passport issued by the French ambassador, suggesting that he intended to flee the country.

Corder was returned to Suffolk and confined at Bury St Edmunds while preparations were made for his trial. By this time, lurid accounts of the murder had circulated far and wide. Interest was stirring beyond the boundaries of rural Suffolk.

A journalist named James Curtis wrote a lengthy account of the business, talking to Corder himself and spending two weeks in Polstead. The press, both London and local, feasted on the story, some vilifying the defendant before the case had been tried.

This murder, which sounded like the plot from a penny gaff theatre, was itself turned into a play before Corder even came to trial. These were the beginnings of an industry which would soon churn out memorabilia, from ballads and broadsides, peep and puppet shows to pottery models of the Red Barn and full-blown melodramas.

Amid unparalleled excitement, William Corder finally came to trial on August 7, 1828. The town was packed, interested parties and sensation seekers from London and further afield filling the hotels which adjusted their prices accordingly.

Admission to the trial would be by ticket only and women would be denied entry. Such was the fascination in the case that it took officials almost half an hour to push their way through surrounding crowds and enter the courtroom.

William Corder, attired in a new suit of clothes and wearing the glasses which lent him a studious appearance, looked pale as he listened to the ten counts of murder being read to the court. The Crown was playing it safe and there was small chance of Corder evading all charges.

After the case against him had been made, Corder himself offered his own defence, in which he protested that opinion had been perverted by newspaper reports published before the trial. "By that powerful engine of the press," he said, "I have been described...as the most depraved of human monsters."

The defendant made an articulate defence and some witnesses did take the stand to testify to his character. But weighing against him was a formidable amount of circumstantial and medical evidence.

Though the exact cause of Maria's death remained unproven, Corder was found guilty and the judge, Chief Baron Alexander, sentenced him to hang. He further decreed that his dead body be dissected and anatomised.

Corder, who had maintained his composure up to this point, now appeared to falter. Hanging was one thing but to be dissected and denied a grave was too much. With unseemly haste, the date for the execution was set for only three days later.

Corder's execution was as sensational as his trial and the reports it generated.

Spectators eager for a good spot began turning up early on the morning of Monday, August 11 and the crowd in and around the prison, (estimated by newspapers at between 7,000 and 20,000) was great enough for a new door to be made in a side wall to allow the execution party direct access to the gallows.

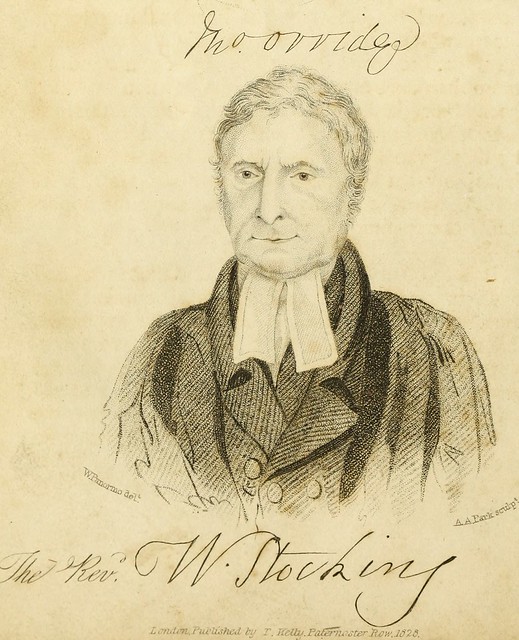

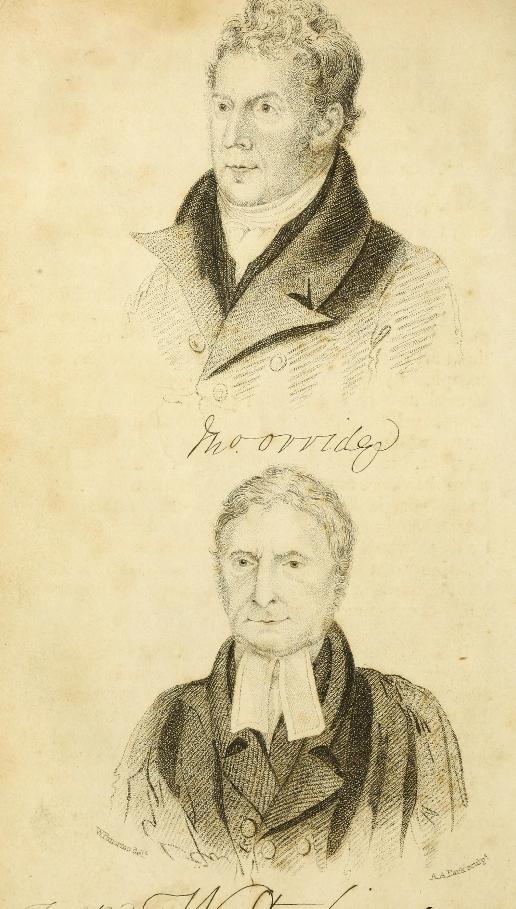

Corder had spent his final days in agonies of uncertainty. The prison chaplain and John Orridge, the prison governor, had been persistent in their attempts to obtain a confession from the condemned man, efforts which finally paid off when Corder admitted to accidentally shooting Maria during a quarrel. He denied stabbing her.

Corders death was not an easy one. Once dropped, the hangman held his legs while he died. A convulsion was recorded ten minutes later. After the body had been suspended for an hour, it was taken down and transported to Shire Hall, where an incision was made along the abdomen to expose the muscles.

As many as five thousand people filed past, eager to set eyes on the corpse of the man who had murdered Maria Marten.

Despite Corder's coerced confession and a last statement which was prompted by John Orridge, a few doubts have lingered.

These have focussed in particular on Maria's stepmother and her extraordinarily prescient dreams. Maria's stepmother was only a year or so older than Maria and was rumoured to also have formed an amorous connection with William Corder. It has been noted that her dreaming began just as news might have reached her of Williams marriage to Mary Moore. Might she have known much more than she was letting on?

And why did William arrange to meet Maria in the Red Barn in front of her mother?

No-one will ever know exactly what William Corder did at Polstead that day, but one thing is for sure; people will continue to stand before the grimly realistic bust in Moyses Hall and ponder on events surrounding the Murder in the Red Barn for a very long time to come.